An alternative history of graphic novels

The common history of graphic novels, and the one I learned, follows comics aimed mainly at children and the publishers who made them. We hear about the rise and fall of EC, the birth of Mad, the undergrounds, Will Eisner, and then we miraculously get to Maus. This history isn’t wrong so much as the work it presents is very conscribed. Gil Kane’s Blackmark may have broken new ground, but it was basically an extension of the kind of adventure stories already being told in comics. Even the comics of the underground movement were just a step away from the work in Mad Magazine.

This is why I’ve always been excited to find works that fall completely outside this established narrative. Often, these works come out of the art world, not the publishing world. They are usually aberrations, almost never inspiring other works. Because of this, they don’t fit neatly into a causal narrative of the graphic novel. Yet for those of us who are creating today, these earlier works provide both inspiration and proof that comics can go in completely unexpected directions.

I just want to quickly mention that this is not meant to be a complete list. These are simply works I have discovered over the years and have found inspiring. Still, if you know of some other work that would fit here, please feel free to mention it in the comments.

Simplicissimus

Simplicissimus was a German magazine started in 1896 that was often critical of the politics of its day and ran work by writers such as Thomas Mann and Rainer Maria Rilke. It also featured artwork by people like Kathe Kollwitz and George Grosz. It also had comics. Yes, of course, it had cartoons, many satirical. But it also had multiple panel comics by artists such as Bruno Paul and Olaf Gulbransson. It’s not so much the subject matter of these comics that I find so inspiring, but their style. It’s German Expressionism brought to bear on comics. The only similar approach is Lyonel Feininger’s on The Kin-der-Kids.

You can view all the old issues here.

L’Assiette Au Beurre

L’Assiette Au Beurre was France’s answer to Simplicissimus and looked very similar. Again, the magazine was mostly full-page satirical illustrations. Yet every now and again there would be multiple panel strips, most notably by Caran d’Ache.

You can view individual issues by date here.

Frans Masereel

Masereel was a Flemish woodcut artist who worked mostly in magazines. Yet at some point he decided to make a series of woodcuts and publish them as wordless novels. The first of these, 25 Images of a Man’s Passion, was published in 1918. Yet he is best known for his 1919 work, Passionate Journey. The story spans 165 woodcuts and captures politics, culture, and the unyielding spirit of the individual. It uses images both representationally and metaphorically. It’s an incredible tour-de-force and a must-read for anyone who wants to make graphic novels.

Lynd Ward

Ward followed in Masereel’s footsteps, and while he also had similar political interests, his stories became more layered and subtle than Masereel’s. This culminated in Ward’s 1937 book, Vertigo. The book portrays a narrative from the view of three different characters, each with their own time frame: years, months, and days. It’s an ambitious work and unlike anything else before or since. Ward remained an artist for decades afterwards, mostly doing book illustration. To my knowledge, he did at least one other wordless novel, The Silver Pony in 1973.

Miné Okubo

As I mentioned before, in middle school I was told that Farewell to Manzanar was the only novel written about the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. Yet No-No Boy was published almost twenty years earlier in 1957. And even before that, in 1946, there was Miné Okubo’s Citizen 13660. The book captures the steps that lead up to the internment and the realities people faced once they were interned. I don’t know if Spiegelman read this or not, but Citizen 13660 is a spiritual mother to all the autobiographical graphic novels that would come decades later.

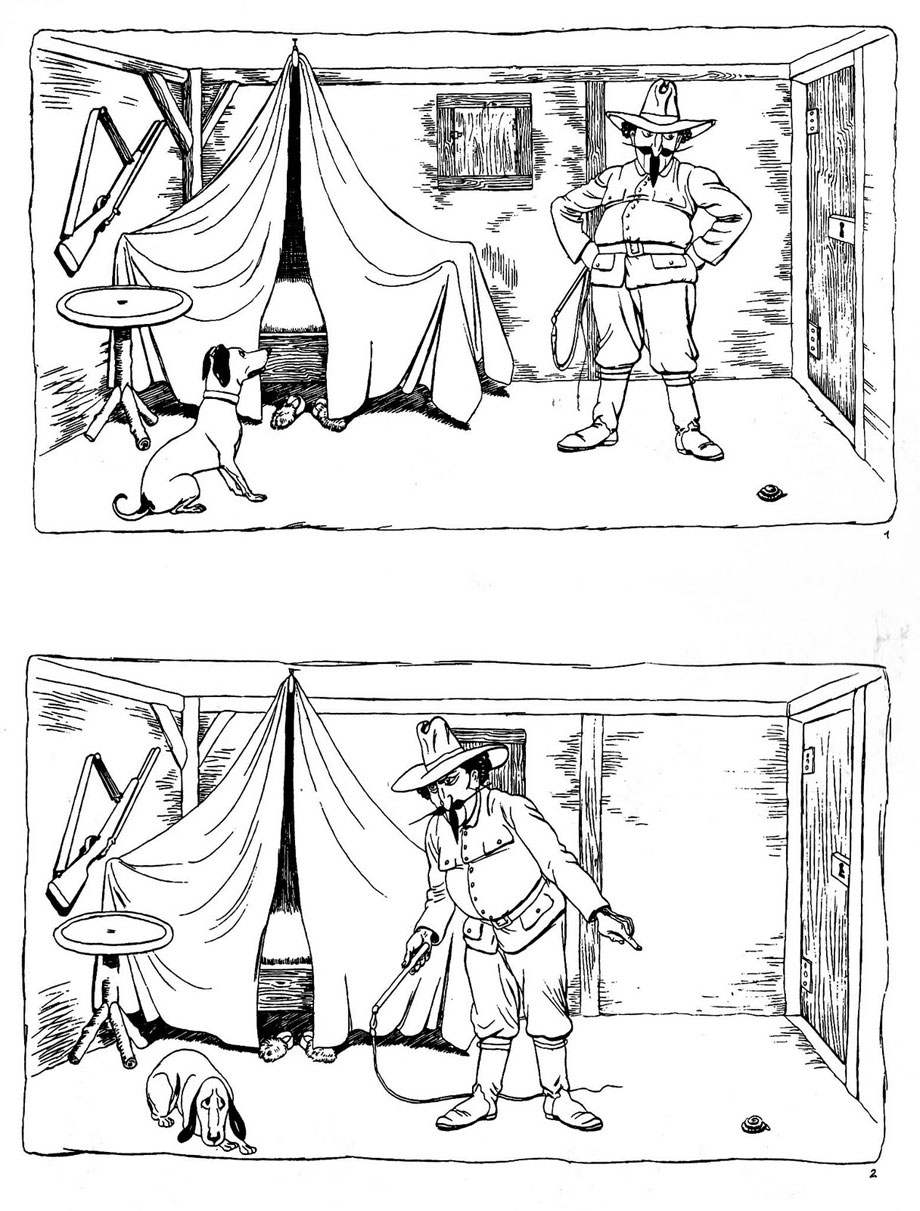

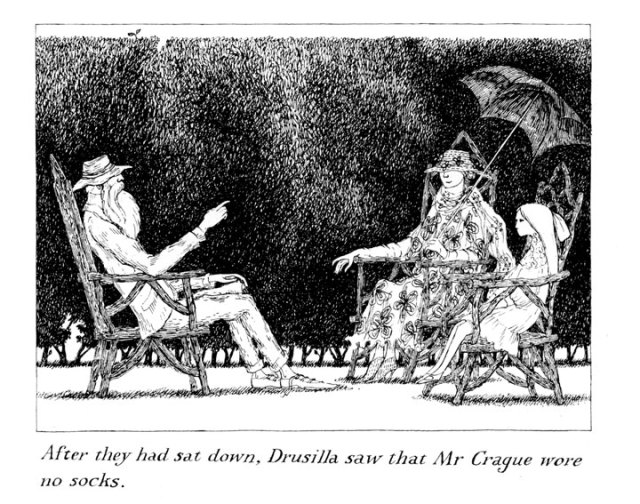

Edward Gorey

My parents had a few of the Gorey collections, Amphigorey, and so personally his work is some of the first comics I ever read. It took me a long time to realize that they were comics, though. The Gashlycrumb Tinies seemed to have no relation to Daredevil, which is the first comic book I began reading. Again, Gorey is not part of the standard comics narrative. But of course his work is comics. He first began publishing his macabre little books in 1953. In 1965 he published The Remembered Visit. While this story has the Edwardian characters that populate all his works, it isn’t morbid or humorous. Instead, it’s a quiet little tale of youthful promises and adult regret. It’s surprisingly emotional.

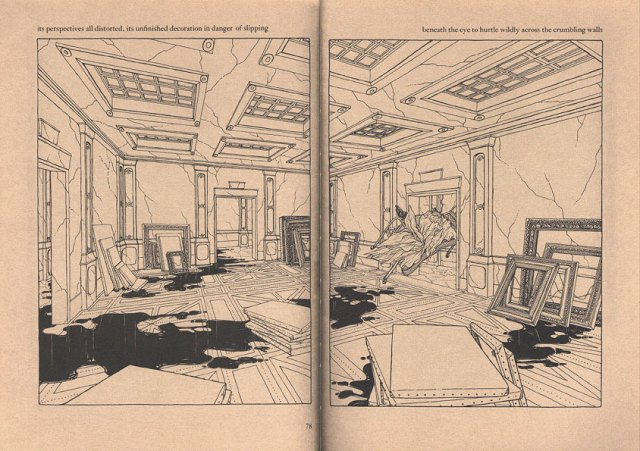

Martin Vaughn-James

Some people argue whether or not the works of Vaughn-James are comics. While not narrative, they contain pictures and words deliberately put into sequence. They have too many images to be poetry and too much sequence to be simply a collection of drawings. Vaughn-James’s work reminds me a bit of the psychedelic comics of Victor Moscoso in Zap Comix, but taken even further. 1975’s The Cage is the longest and best known work by Vaughn-James and it’s difficult to describe. I tried to write a review of it once and fell short. So I’d say it’s just a work that you have to experience. If you’re an artist it will open you up to completely new possibilities for the medium.

There are other names that could be here, like Dino Buzzati, Guy Peellaert, and Milt Gross, but I wanted to stick to artists I was personally inspired by. Still, if you can think of names that fit here feel free to comment.

Thank you for this article. When I kept stumbling on Steinlen’s studies and sketches (https://i.pinimg.com/originals/7f/60/94/7f6094b010db87af08d9889239e55a03.jpg) or various pages from Simplicissimus (that feature Schulz page marked me a lot) I understood that we need to have, if not an alternative history of comics and graphic novels, than at least a much broader one.